Which Scope Reticle Should I Buy?

Posted by Monstrum on Jan 28th 2026

Just when you’ve settled on a new optic you want, you find yourself faced with yet another question: “Which reticle should I buy?” If you’re having trouble deciding you’re not alone, these days there are more types of reticles to choose from than ever before. Here we’ll review the different types of reticles and some of their subtypes so you can find the perfect match for your use case.

While this article will broadly cover most modern available options, it is not intended to be an exhaustive guide on every reticle ever made (we’d need a book for that). For that reason, we’re going to focus mainly on current production reticles that are popular within the U.S. commercial market.

History of Reticles

Like many of history’s greatest inventions, the optical principles behind modern riflescope reticles were discovered by accident. William Gascoigne, a 17th century English astronomer, was looking through his telescope one day when he discovered a spider had spun a web inside its case. When he looked through it, he realized that the web was in focus with distant objects—this was the foundation of history’s first reticle: the cross hair.

Early rifle scopes were around as far back as the 1830s, but they were one-off custom pieces that were not practically effective. It wasn’t until the mid 19th century and the American Civil War that telescopic sights began to see widespread adoption and use. The earliest scopes featured a simple fine cross hair style reticle which is merely two thin lines intersecting at a perpendicular angle. Ironically, the earliest rifle scope reticles were made from hair (hence the name) or spider web as the original had been.

As firearms improved in accuracy and manufacturing standards got better, reticles became more sophisticated. By the Second World War, various countries began adopting their own reticle styles to suit their needs—the German Post Reticle was one such example which uses heavier lines that stand out better in low light and a central post with a sharp point coming up from the bottom which allowed for rudimentary range finding.

It was not until later in the 20th century that rifle scope reticles really began to evolve into complex families we know today. With the level of precision that late 20th century rifles could afford, optics evolved to give shooters better range estimation capabilities and markings denoting bullet drop at specific distances and wind holds for given speeds.

First Focal Plane and Second Focal Plane Optics

Before you decide on which reticle to buy, you should first consider whether or not you want a first or second focal plane scope. If you’re not familiar with these terms, here’s a quick rundown.

First or second focal plane refers to which focal plane a magnified optic’s reticle is focused on within the scope. Traditionally, all rifle scope reticles were focused on the second focal plane, but as reticles and manufacturing technology improved, first focal plane scopes evolved to make range estimation easier with variable magnification. We’ll explain in greater detail how range estimation works later, but essentially, the process requires measuring a target against precisely calibrated markings within the scope’s reticle—the settings on which a scope’s markings are accurate depend on whether it has a first or second focal plane reticle .

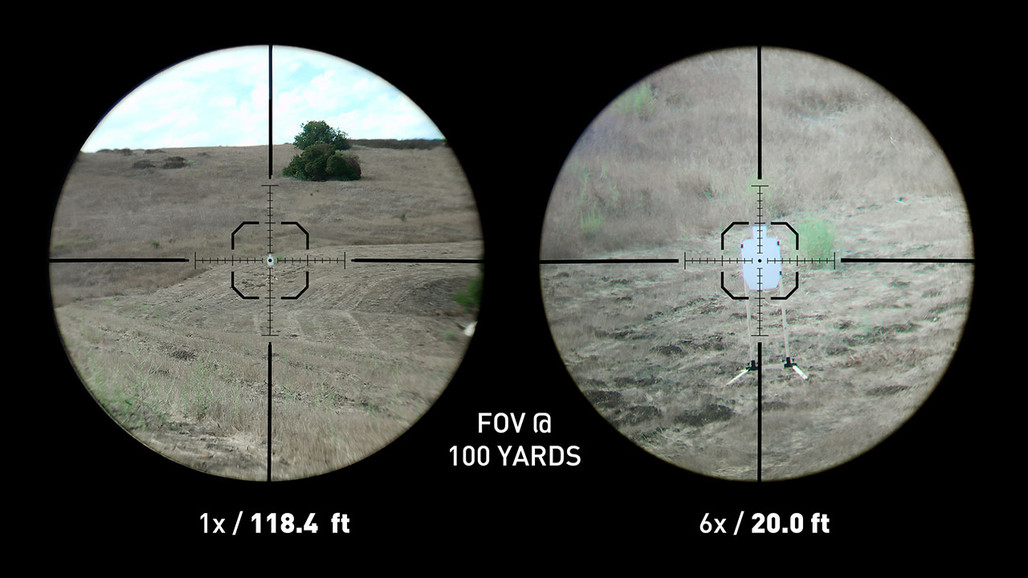

These days, most scopes have some degree of variable magnification meaning you can adjust a dial to zoom the scope in or out. On second focal plane (SFP) scopes, the reticle will remain a consistent size as you look through the eyepiece from lowest magnification to the highest magnification. By contrast, the reticle on a first focal plane (FFP) scope will appear small on the scope’s lowest magnification size and grow proportionally to your magnification setting getting larger at the highest.

While it may not seem like a big difference at first, this key distinction means that FFP optics can be used for range estimation at any magnification setting because the reticle’s markings stay at a consistent size no matter what. SFP scopes on the other hand can only be used to estimate range at a single magnification setting (usually the highest) because the markings on the reticle will only be accurate at one point in their magnification.

In most cases, first focal plane scopes are superior to second focal plane scopes for range estimation, but if you don’t need your scope for this, second focal plane scopes are less expensive because they are simpler and easier to manufacture.

Because they have to work equally well both zoomed out and zoomed in, first focal plane reticles are usually much more complex relying on clever design features like large outer rings that are visible on low magnification in addition to finer detailed markings that become more visible as you zoom in.

A typical FFP scope will look almost like a red dot sight with a bright center on the lowest magnification that becomes a large outer ring with finer markings you’ll be able to discern as you increase in magnification. These days, the deciding factors between first or second focal plane reticles typically come down to complexity and cost.

Scope Reticle Types

Crosshair Reticles

To this day, the crosshair reticle, directly descended from the earliest rifle scopes, remains a popular choice for precision rifle shooters and hunters, though modern improved versions have overtaken the original “fine crosshair” in terms of popularity. While crosshair reticles have the advantage of speed and simplicity, they require more guesswork from the shooter in terms of bullet drop and holdover, but in exchange, they offer a simple, clean, and unobstructed sight picture.

Duplex

For hunters, the Duplex crosshair retains the simplicity of a simple crosshair, but adds a bit of range finding capability thanks to its thicker segments outside of the fine center. Duplex reticles can be used for estimating range by using the set distance between the thick part of the reticle and the reticle’s center as a reference point. Say for example if a hunter were to take aim at an elk and they could estimate the elk’s size with reasonable accuracy, measuring its appearance against the duplex reticle will give the hunter a quick and rough estimation of its distance.

Range Finding Reticles

Taking cues from artillery spotting and land surveying optics, scope reticles evolved to be used as range finding tools. They rely on a simple principle: a target of known size measured against a reticle of known angular width can yield its distance from the shooter with some basic math, though the accuracy of this estimate is only as good as both the initial size estimate and the shooter’s reticle measurement.

To make this range estimation easier, scope reticles evolved to look something like rulers measuring either milliradians or minutes of angle. We’ll cover both styles here.

Mil or MRAD Reticles

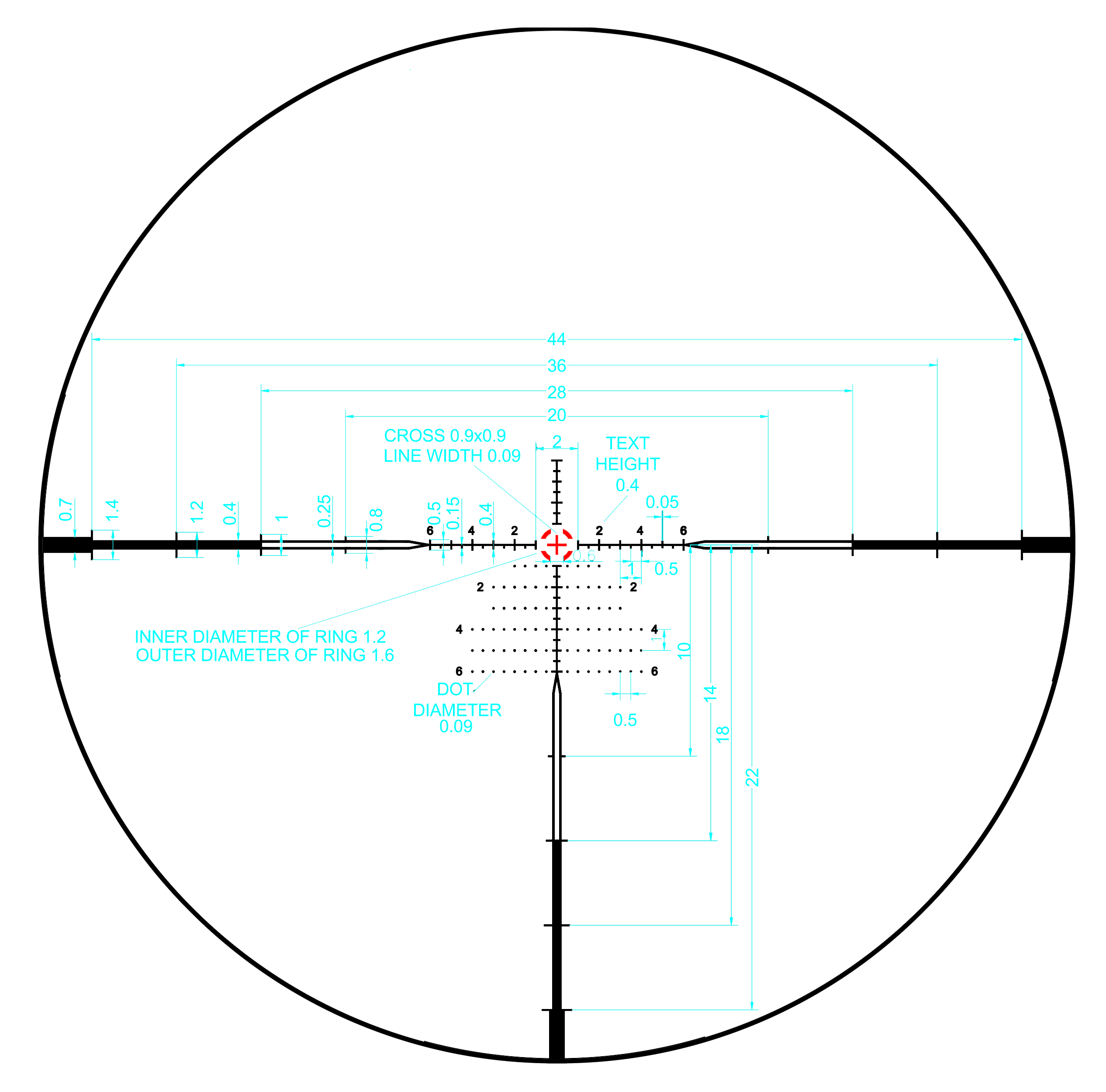

Mil (short for Milliradian) or mil dot reticles are crosshair style but with circles or hashmarks at regular intervals of exactly one milliradian extending out from the reticles center on all four lines. Milliradians are simply a unit of measurement for angles similar to, but different from degrees. The dots/hashmarks on mil reticles can be used for holdover, but they are primarily intended to be used for range estimation just like lines on a ruler, although these denote angle rather than length.

Mil based reticles are able to estimate range because the dots/hashmarks are a known size and distance apart so they can be used in the same way as as a duplex reticle just with more reference points to measure a target with. They can also allow for a higher degree of precision since a target can be measured by the distance between marks or the marks or dots themselves. The dots within traditional mil dot reticles for example are 0.2 mils in diameter. A shooter who is well practiced with mil or mil dot reticles can quickly estimate range using a reasonably accurate estimate of the target’s size and its appearance measured mils by using the mil relation formula which works like this:

(Range = Size / Mils) *provided you use the exact same unit of measurement for range and size

Translated and simplified for use in yards, here’s what the formula looks like:

Range (yards) = (Target Size (inches) * 27.7778) / (Target Size (mils))

MOA Reticles

MOA reticles work in exactly the same way as mil or mil-dot reticles, except they are segmented based on minutes of angle instead of by milliradians. Much like the empirical measurement system vs. the metric system, minutes of angle (MOA) are simply another system for measuring angle based on degrees instead of milliradians. Here’s a breakdown of how the two are different: A single degree of angle consists of 60 arc minutes, a single one of these minutes is referred to as one minute of angle. Milliradians on the other hand are 1/1000th of a radian. They work via proportions, one milliradian is equal to one foot at a distance of one thousand feet, one yard at one thousand yards, and so on.

MOA is the more traditional system that American rifle scopes have historically used as the basis for their adjustments, though many argue that the mil system is simpler and in most cases faster for quick mental math. One nice advantage of MOA reticles is that the click adjustments for windage and elevation (typically ¼ or ⅛ MOA) use the same system as the reticle’s range finding which can get confusing if you’re using a mil-dot reticle that has MOA click adjustments, though these days scopes are made with mil click adjustments too.

Regardless of which system you choose, training is key and dedicating time and effort to knowing how your reticle works is more important than which one you end up choosing.

BDC Reticles

BDC stands for bullet drop compensated. This refers to reticles that have markings or stadia for bullet drop of known calibers at set distances. These can be as simple as two or three extra bars or dots intersecting the bottom line below the reticle’s center, or they can include “christmas tree” style reticles which have dozens of reference points coming down in a christmas tree pattern below the center aiming point. We’ll discuss some of the more popular types here.

Simple BDC Reticles

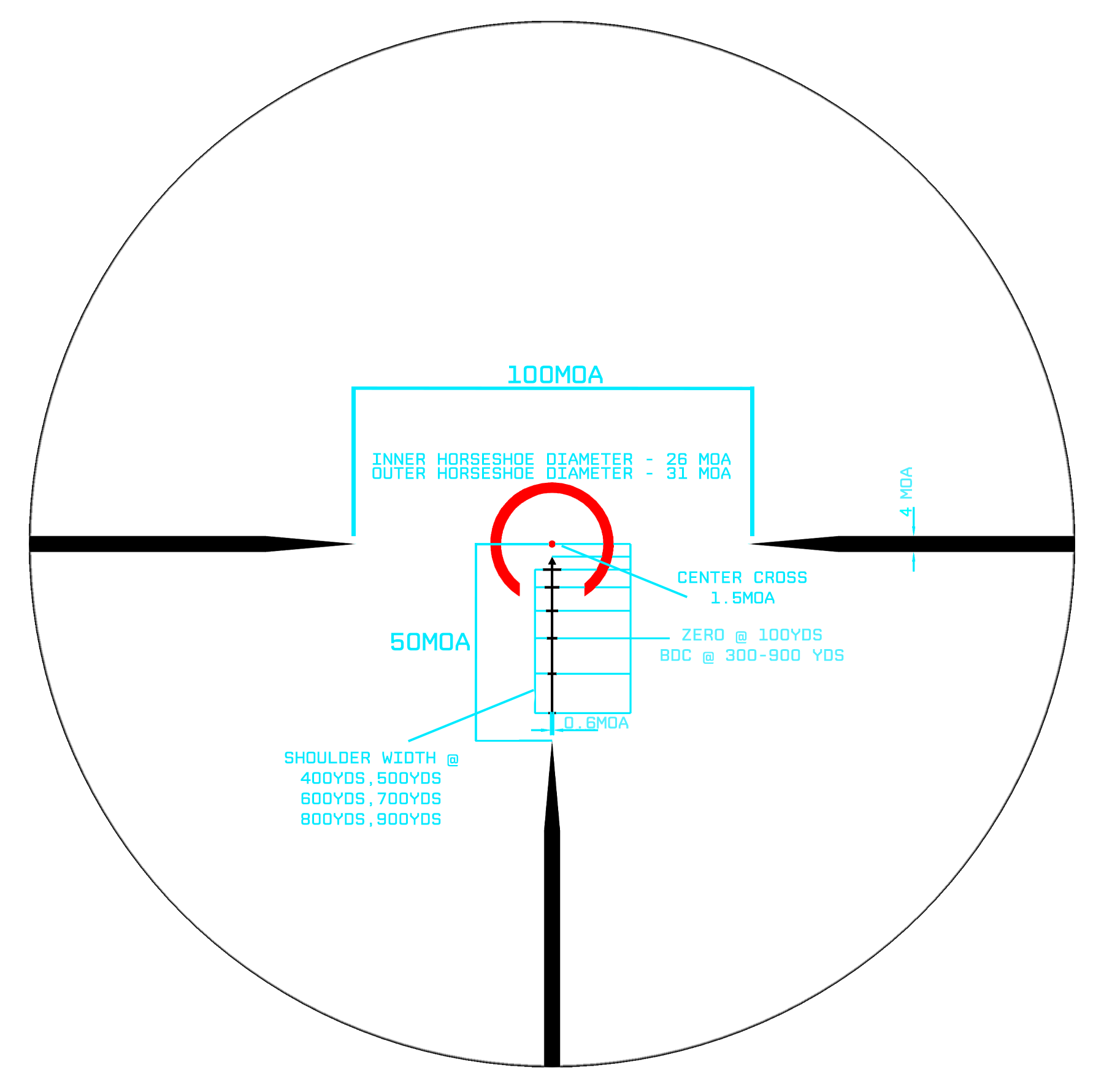

Most reticles used on tactical rifles these days have some manner of BDC markings because they are extremely fast, simple, and easy to use assuming you have the right reticle for the caliber you’re shooting. One of the most popular simple BDC reticles is the chevron style reticle used in the Trijicon TA31 ACOG prism scope.

The 4x version of the ACOG used by the U.S. Marines has a chevron reticle center point and five lines intersecting the vertical line below it at irregular intervals. When the optic is mounted to the exact rifle (M16A4) shooting the exact ammo (M855 62-grain) it was designed to work with and zeroed at 100m, these intersecting lines fall at the points where a bullet will impact at 400, 500, 600, 700, and 800 meters respectively. If you can guess with reasonable accuracy how far your target is away from you, just hold over on the correct hash mark and your shot should hit assuming there’s no wind. We mentioned the ACOG as an example here because it’s a popular reticle that most would be familiar with, but many other rifle scopes use simple BDC reticles that work very similarly.

Simple BDC reticles usually have some rudimentary means of range estimation, though these are typically simplified and less capable than a true range finding reticle. The TA31 ACOG for example uses varying widths of the BDC markings that are supposed to approximate shoulder width of an average sized man at those distances—but you can see where this system would struggle if the target is either not average sized or not standing squared off to the shooter.

BDC reticles are popular for tactical rifles because they work best with specific calibers they were made for—it is also for this reason that these reticles are popular for service rifles among the world’s military powers. What simple BDC reticles lack in versatile range finding capability, they make up for in speed and efficiency provided you are using the correct caliber and a comparable barrel length to what the reticle was designed for. The other main limitation of simple BDC reticles is that while they can easily visualize bullet drop, they don’t usually show you the effects of wind drift. This shortcoming is solved by another reticle design: the Christmas tree.

Christmas Tree Reticles

Christmas tree reticles resemble simple BDC reticles with one key difference: they have extra markings extending horizontally from the vertical bottom line denoting wind drift that become wider toward the bottom. The result is a cross hair or center dot style reticle that has markings in a triangular shape beneath vaguely resembling the shape of a Christmas tree. These markings are there to visualize how a steady wind of known speeds (often 5 or 10 miles per hour) blowing at exactly 90 degrees of your bullet’s flight path will cause it to drift. The markings get wider toward the bottom because as the bullet loses velocity and the wind has a longer time to affect its flight path, its wind drift increases dramatically.

While Christmas tree reticles can be fast and effective under the right wind conditions, they have two limitations over other styles of reticles. First, if the wind isn’t blowing at exactly 90 degrees of your bullet’s flight path (snipers refer to this as a “full value”), the reticle’s hashmarks can become a complicated and distracting mess. If you have a good read on the wind’s direction, you can theoretically hold halfway to the correct hashmark under a “half value” wind or a quarter way in a “quarter value” wind, but you can see how all those extra markings start to blur together under field conditions—this is where the fine line exists between busy and clean reticle designs which brings us to the second drawback of Christmas tree reticles: complexity.

At the end of the day, a rifle scope is a tool designed to make aiming precisely and accurately easier. Wind is a far more difficult variable to approximate than bullet drop and for this reason, reticles that opt to include christmas tree markings tend to become very busy and therefore slower to use. Under ideal conditions, they can be very fast and they can also help newer shooters visualize the effects of wind drift at range, but under non-ideal conditions, only experienced shooters who can accurately ascertain wind speed and direction should expect to get the most out of a Christmas tree reticle.

Because Christmas tree reticles have so many markings, they are usually relegated to long range precision rifles rather than tactical or competition rifles. For an example of what these reticles look like, check out our Beast 5-25x56mm FFP Rifle Scope. When speed is a main consideration, a less complex reticle is desirable.

Close Quarters Reticles

If you’re setting up a rifle for close quarters out to medium range shooting, what you want is a simple, clean, and brightly illuminated reticle that isn’t overly busy with distracting markings you probably won’t need. This is precisely what close quarters reticles are optimized for.

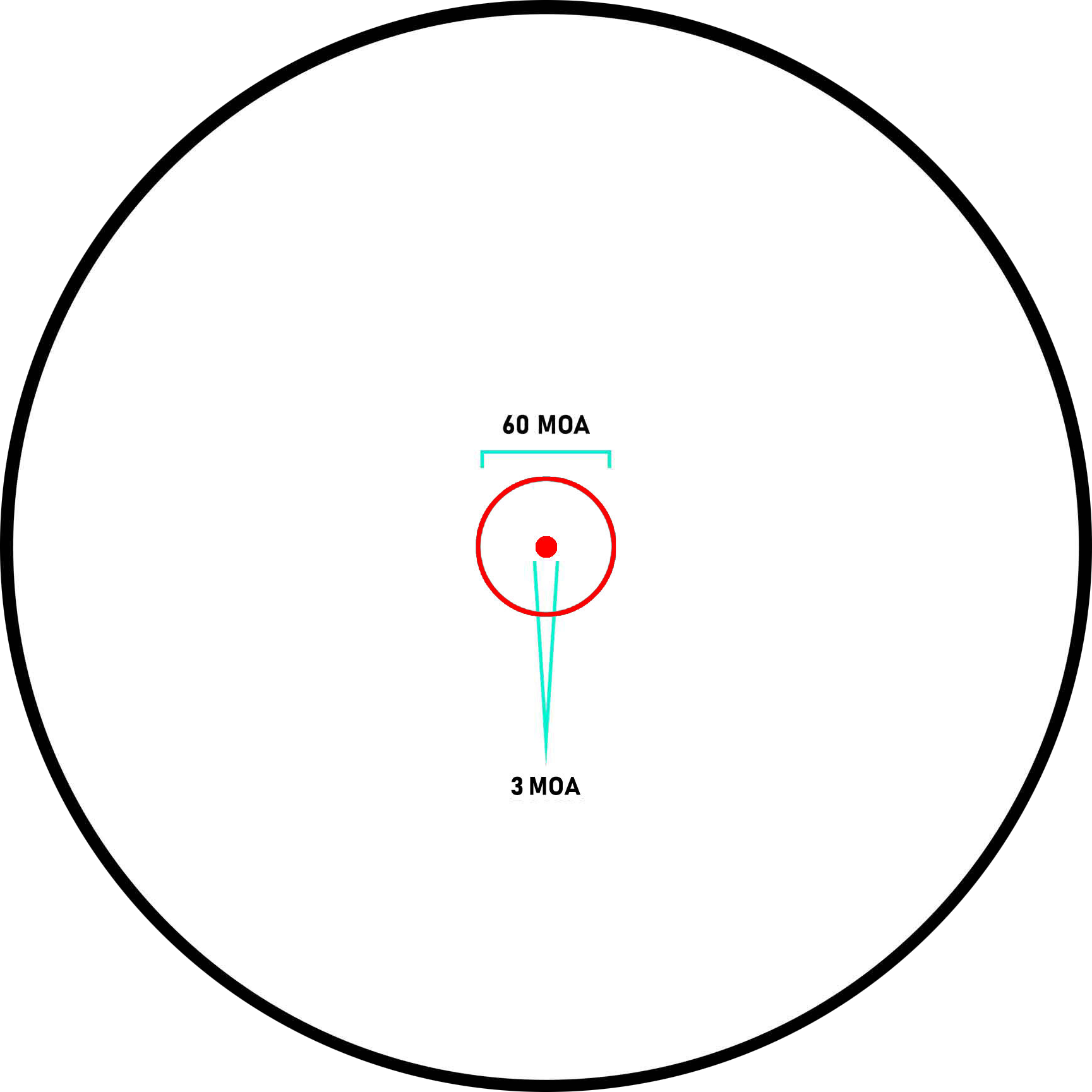

Most reticles in this category are found on red dot sights, holographic sights, prism scopes, and some rifle scopes (usually LPVOs). There are many variants of close quarters reticles, but some of the most popular include circle dot or horseshoe style reticles, both of which have a small center point surrounded by a wider and sometimes thicker outer ring. The chevron style of the Trijicon ACOG we mentioned earlier could fall within this category, although modern close quarters reticles usually also have a ring or similar shape surrounding the center point because it makes shooting at very close ranges faster. The primary purpose of these large rings is faster pickup for the eye—it’s far easier and faster to put a large ring on your target than a fine point, but they are also easier to make brighter since illumination usually relies on reflecting light back into the shooter’s eye and more surface area means a brighter reflection.

While some close quarters reticles incorporate BDC or other markings, the majority trade complexity for simplicity and usually only rely on either the center aiming point (if it's a chevron or dot of known size) and the outer ring/horseshoe itself for very crude range estimation. One other use case for large outer rings found on reticles designed for close quarters use is that the bottom of the large ring can be used as an indexing point for extremely close quarters shooting. One example of this is the EO Tech holographic sight. When mounted on an AR-15 style rifle and with the center point zeroed at 50 yards, the bottom of the ring is where your shots should impact at 7 yards.

For a visual example of a circle dot style close quarters reticle, check out our Ares V2 Red Dot Sight or our Marksman 3x Prism Sight.

Conclusion

Whether you’re looking for a simple and clean cross hair reticle or a more complex, but capable range finding reticle, choosing the right one depends on what you need your scope to accomplish. We’ve discussed first vs. second focal plane reticles, how range finding works, and the pros and cons that come with both complicated styles like Christmas tree reticles and also clean styles like those designed for close quarters.

If you’re looking for the perfect reticle for your new rifle scope, check out our full line of rifle scopes, red dot sights, and prism scopes which can be filtered by reticle to find the perfect match for you.